Among the ergogenic nutritional supplements, creatine is definitely the most well-known and popular among athletes.

It might just be the most studied supplement on the market and boasts a large amount of scientific studies that have confirmed its benefits, studying its risks and collateral effects. Without a doubt, creatine is among the few supplements that has a documented benefit, not just in athletes, and with well defined dosage and consumption protocols.

In a world of supplements that gets bigger practically every day with new substances that promise miraculous results, we can feel safe integrating creatine into our nutrition protocol.

- What purpose does creatine and its supplementation have?

- The benefits of creatine supplementation

- Forms on the market and consumption protocols

- Creatine and women

- False myths and possible collateral effects

What purpose does creatine and its supplementation have?

Its use is widespread among those who work out regularly, but first let’s talk about what creatine is. Biochemically speaking, it’s a member of the guanidine family and is a naturally occurring non-protein amino acid found naturally in mainly red meat and seafood. Around 95% of creatine of the body is found in skeletal muscle and about 5% in the brain and testes. Two thirds of the intramuscular creatine is phosphocreatine (PCr), while the rest is free creatine.

Around half of the daily requirement of creatine is satisfied by animal sources in our diet, the remaining amount is mainly synthesized in the liver by arginine and glycine.

So what’s creatine’s purpose, especially from a sport point of view? Its supplementation has a direct and main effect on the increase in concentration of intramuscular creatine with the following effects:

- increase lean and muscle mass

- increase performance, including weightlifting and aerobics

- better performance in single and repeated sprints

- better adaptation to training, a better capacity to manage elevated volumes of work

- better recovery post workout

- injury prevention

- better glycogen synthesis and hydration

- better thermoregulation and tolerance to trainings at high temperatures

To put it briefly: creatine serves to give energy to the body and ensure optimal performance during training.

The benefits of creatine supplementation

The benefits of creatine monohydrate go above just the muscular level and PCr levels, therefore, improving exercise and high-intensity training. Research has clearly shown several beneficial aspects on health in general and/or potential therapeutic effects.

Although more research is necessary to further explore its potential beneficial effects, based on the available evidence, the supplementation of creatine appears to increase the availability of cellular energy and support general health, physical shape and wellness for life and help maintain or increase muscle mass in elderly individuals.

Furthermore, creatine supplementation during weight loss due to energetic restriction can be an efficient way to preserve muscle during the diet.

The supplementation of creatine can support cognitive functioning, in particular with aging and a healthy management of glucose.

The long-term integration of creatine and at high doses in individuals lacking creatine synthesis can increase their levels of cerebral creatine and PCr and reduce the gravity of deficits associated with these illnesses.

Ensuring good levels of creatine can have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. In fact it represents an important source of immune cell energy, and can help maintain a healthy immune system and have anti-cancer properties.

It can improve the functional capacity in patients with chronic illnesses and syndromes correlated to fatigue like post-viral fatigue syndrome (PFS) and myalgic disease and encephalomyelitis (ME).

Creatine can also support mental, reproductive, and skin health.

In an omnivore diet that intakes around 1-2 g a day of creatine from mainly animal origin, the reserves of muscular creatine are saturated for about 60-80%. As a result, the nutritional supplement creatine serves to increase the muscular creatine and the PCr by about 20-40%.

Forms on the market and consumption protocols

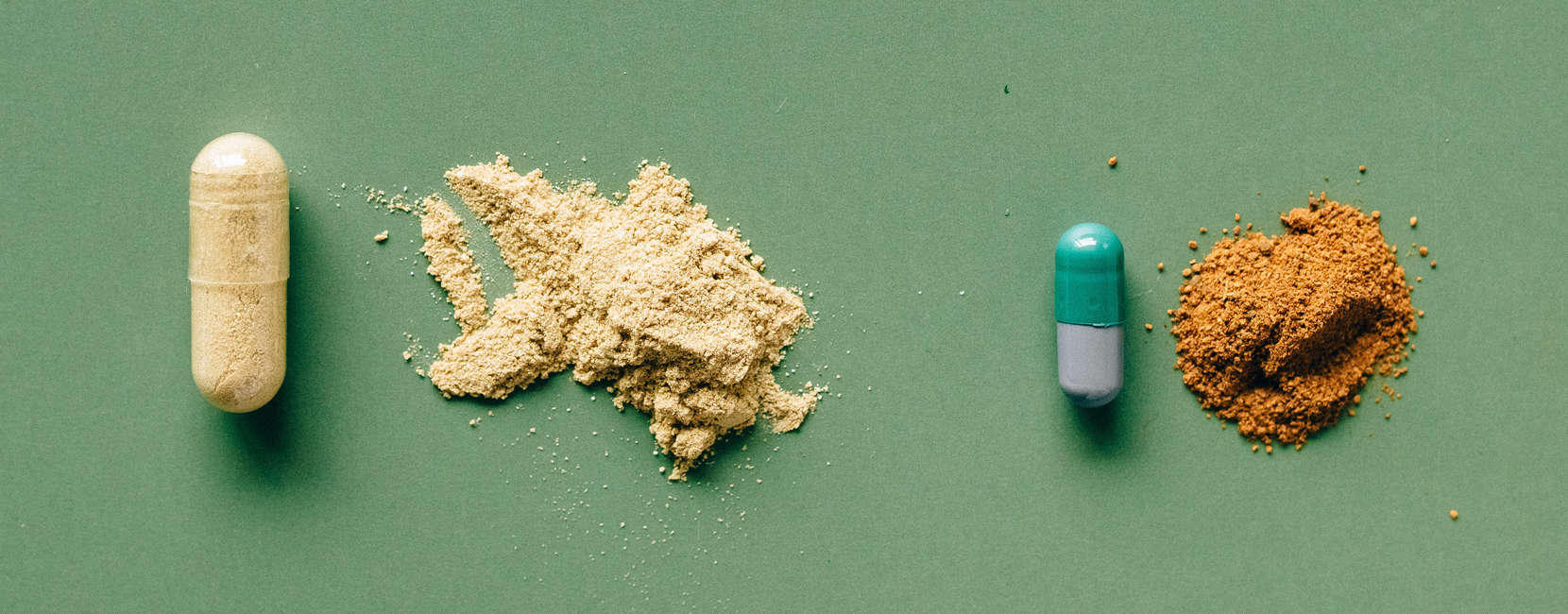

Various forms of creatine exist, put on the market after the most famous and well-known monohydrate form, like the citrate creatine, the buffered creatine or the creatine pyruvate.

These forms were developed to improve the solubility and efficiency, often with little success. At the moment, the monohydrate creatine remains the most studied and clinically efficient form in terms of muscle absorption and capacity to increase the intensity and capacity of exercise, and no other mentioned form has shown greater effects. It’s important to make sure that you always use a form that’s safe and registered.

Regarding dosage and consumption protocols, when should it be taken? The most tested and safest at the initial load followed by a maintenance phase or the no-load protocol called “Short & High”.

In a preparation that’s been programmed in advance, it’s opportune to consume creatine in a loading and maintenance protocol, in order to guarantee better long term results and expects an initial phase of 5-7 days with a daily amount of creatine equal to 0,3g/kg per lean mass divided in 3-4 daily consumptions, followed by a maintenance of 3-5/gr per day for the duration of the preparation.

In the absence of time or for competitions/performances not programmed, its recommend to take 0,3g/kg of lean mass divided in 3-4 daily consumptions during training days for 5-10 days up until the event.

The addition of carbohydrates or carbohydrates and proteins during the consumption of creatine appears to increase the muscle absorption of the creatine. This is why it’s better to take it after complete meal, especially if you’re in the maintenance stage, in a shaker with protein (30-50 grams according to the requirement) and sugars/carbohydrates (70-100 gr) post workout in a shaker with water and carbohydrates during training for better recovery. In fact, it’s been shown that the consumption of a protein-based drink, glucose, and creatine before and after exercise, after 10 weeks shows a better retention of creatine in the muscles, an increase in lean mass and strength, and a small loss in fat, compared to drinking the same drink in a different moment of the day.

Creatine and women

Considering the physiological difference between men and women, creatine supplementation in women needs particular attention.

In fact, women show a reduction of 70-80% of endogenous creatine deposits compared to men. As a result, it’s evident that due to changes correlated to hormones and kinetics of creatine and phosphocreatine resynthesis, supplementation may be particularly important during menstruation, pregnancy, postpartum, during and after menopause. It appears that creatine supplementation among women in pre-menopause has benefits. For example, the women in post-menopause can experience benefits in the dimension and function of the skeletal muscle and favorable bone effects when they consume high doses of creatine combined with endurance training.

False myths and possible collateral effects

After having examined the effects and ways of consumption, let’s debunk some of the myths about the collateral effects of habitual use of creatine. Strong evidence in literature demonstrates that the supplementation of creatine doesn’t lead to water retention, dehydration or muscular cramps, nor damage of dysfunction of the kidneys in healthy individuals, even if consumed in high quantities.

In conclusion, integrating creatine can give great muscular advantages in terms of performance in strength athletes like endurance, can be very useful in a wide variety of athletic and sports activities and creates multiple advantages and benefits for women and elders during their lifetime and in a series of pathological conditions.

Bibliography

- Bertin M, et al. Origin of the genes for the isoforms of creatine kinase. Gene. 2007;392(1–2):273–82.

- Suzuki T, et al. Evolution and divergence of the genes for cytoplasmic, mitochondrial, and flagellar creatine kinases. J Mol Evol. 2004;59(2):218–26.

- Sahlin K, Harris RC. The creatine kinase reaction: a simple reaction with functional complexity. Amino Acids. 2011;40(5):1363–7.

- Harris R. Creatine in health, medicine and sport: an introduction to a meeting held at Downing College, University of Cambridge, July 2010. Amino Acids. 2011;40(5):1267–70.

- Buford TW, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: creatine supplementation and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2007;4:6.

- Kreider RB, Jung YP. Creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2011;15(2):53–69.

- Kreider RB, Stout JR. Creatine in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2021 Jan 29;13(2):447.

- Hultman E, et al. Muscle creatine loading in men. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1996;81(1):232–7.

- Green AL, et al. Carbohydrate ingestion augments skeletal muscle creatine accumulation during creatine supplementation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(5 Pt 1):E821–6.

- Balsom PD, Soderlund K, Ekblom B. Creatine in humans with special reference to creatine supplementation. Sports Med. 1994;18(4):268–80.

- Harris RC, Soderlund K, Hultman E. Elevation of creatine in resting and exercised muscle of normal subjects by creatine supplementation. Clin Sci (Lond). 1992;83(3):367–74.

- Brosnan ME, Brosnan JT. The role of dietary creatine. Amino Acids. 2016; 48(8):1785–91.

- Volek JS, et al. The effects of creatine supplementation on muscular performance and body composition responses to short-term resistance training overreaching. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;91(5–6):628–37.

- Kreider RB, et al. ISSN exercise & sport nutrition review: research & recommendations. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2010;7:7.

- Branch JD. Effect of creatine supplementation on body composition and performance: a meta-analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2003; 13(2):198–226.

- Lugaresi R, et al. Does long-term creatine supplementation impair kidney function in resistance-trained individuals consuming a high-protein diet? J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2013;10(1):26.

- Kreider RB, Kalman DS, Antonio J, Ziegenfuss TN, Wildman R, Collins R, Candow DG, Kleiner SM, Almada AL, Lopez HL. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017;14:18-z eCollection 2017.

- Cribb PJ, Hayes A. Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006 Nov;38(11):1918-25

- Rawson ES. The safety and efficacy of creatine monohydrate supplementation: What we have learned from the past 25 years of research. Gatorade Sports Science Exchange. 2018;29:1–6.

- Smith-Ryan AE et al. Creatine Supplementation in Women’s Health: A Lifespan Perspective. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 8;13(3):877.

Since 2009, we’ve been by your side, helping you create the perfect training spaces for Cross Training Boxes, Personal Trainer Studios, and professional Home Gyms.

Since 2009, we’ve been by your side, helping you create the perfect training spaces for Cross Training Boxes, Personal Trainer Studios, and professional Home Gyms.